There is an often attributed incident to Draupadi, where she is said to have called Duryodhan a “blind man’s son” after he mistook an artificial pond in their palace at Indraprastha for a crystal floor and slipped into the water. This narrative has been promoted by TV serials, abridged versions, and retellings of the epic. The dialogue that’s popularly used is “Andhe ka putra bhi andha!” It means: a blind man’s son is also blind.

But is this incident really mentioned in the Mahabharata? The short answer is NO — it is not mentioned anywhere in the Unabridged Mahabharata. In the rest of the article, I will describe (with quotes) everything that happened in the Pandava’s palace at Indraprastha, the day after the Rajasuya Yagna, when Duryodhan fell into the indoor pond of water.

I’ll begin with a little background.

The Pandavas established Indraprastha as the capital city of their Kingdom after Dritarashtra gave them the Khandavprastha region, of the ancestral kingdom, as their share. The first goal of the Pandavas was to bring well-being and prosperity to the citizens of the kingdom. After succeeding in this goal, Yudhishthira expressed the desire to perform the Rajasuya Yagna and become the emperor of Bharat. Subsequently, the four Pandavas (Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadev) set out in the four directions, brought all the surrounding kingdoms under their sway, and returned to Indraprastha with large tributes.

Sometime after this, Yudhishthira invited all the kings, who had accepted him as the emperor, and relatives/well-wishers to the final Rajasuya Yagna where he would be crowned as the emperor of Bharat. After the yagna was complete, all the kings returned to their respective kingdoms. However, Duryodhana and Sakuni stayed back to inspect the Pandavas’ magnificent palace.

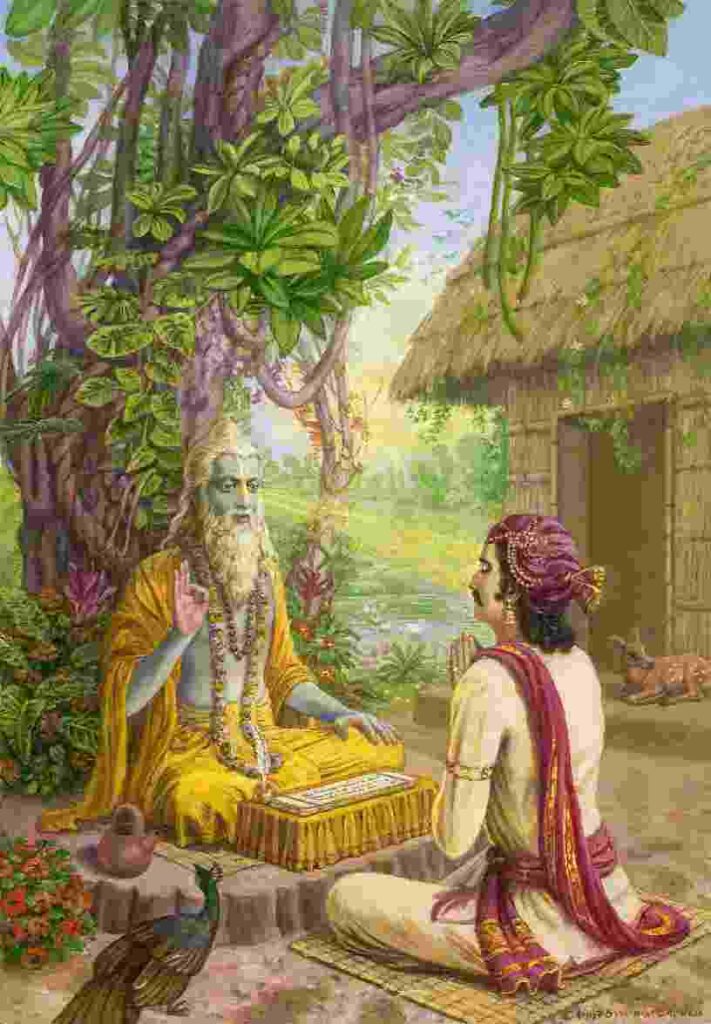

The day after the yagna, Duryodhan and Sakuni walked around the palace and marveled at the extraordinary designs of the kind they had never seen before in Hastinapur. As we will see in the passage below, Duryodhan bumbled a lot in the palace. He mistook the crystal floor to be an indoor pond and he mistook an indoor pond for a crystal floor. As a result, he fell into the water and got himself wet. When the Pandava brothers saw his bumbling, they laughed aloud. Even the menials laughed at Duryodhan.

Unfortunately, Duryodhan’s misery had no bounds because he went on to be further confounded in the palace. He mistook doors for walls and walls for doors, as seen in the passage below. After several such moments, he took leave from the Pandavas and returned to Hastinapur with his uncle, Shakuni.

As we can see, Draupadi was not even in the picture, so there was no question of her insulting Duryodhan and King Dhritarashtra.

Another important point to note (as we will see in future posts) is that Draupadi did not insult the Kuru elders even when she was disrobed after the game of dice, so it’s really far-fetched to assume that she would have uttered unkind words to uncle, Dhritarashtra, and brother-in-law, Duryodhan, in her own palace.

Now, I’ll jump ahead to another passage. Later, when Duryodhan reached his palace, he recounted the incident to his father, Dhritarashtra. In this talk, he mentioned that Draupadi had laughed at him.

See the passage below.

The passage where Duryodhan narrates, to Dritharashtra, how he was insulted.

As we can see in the passage above, the only thing Duryodhana mentioned to his father was that Draupadi and other servants laughed at him. There was no mention of Draupadi calling him a blind man’s son.

This incident of Draupadi telling Duryodhana: “Andhe ka putra bhi andha,” is purely a figment of certain people’s imagination that has been repeated without verification.

Reading the critical edition of the Vyasa Mahabharata will debunk many such ‘common myths’ and help us separate fact from fiction. Check out the English translation of the critical edition by Bibek Debroy. The Mahabharata: Volume 2 covers this incident and more.

The reason why I consider this piece of information important is because the Mahabharata is an epic about the subtle dharma. In certain instances, the subtle dharma is clearly elucidated by Vyasa Muni and, in other instances, it is left to the reader to introspect and decipher the subtle dharma. In this spiritual exercise, the actions, words, and dilemmas of the characters in the Mahabharata become pointers to the subtle dharma (that is described as being beyond human logic and morality). These are small factoids that the reader considers to understand what the subtle dharma might mean. When we twist these seemingly small details, we obscure the subtle dharma that Vyasa-Muni wanted to describe, thus reducing the Mahabharata from being the fifth Veda into being a mere story of the rivalry between cousins.